In this article, I dive into an Olympic event competed by female Artistic gymnasts – the Balance Beam (BB).

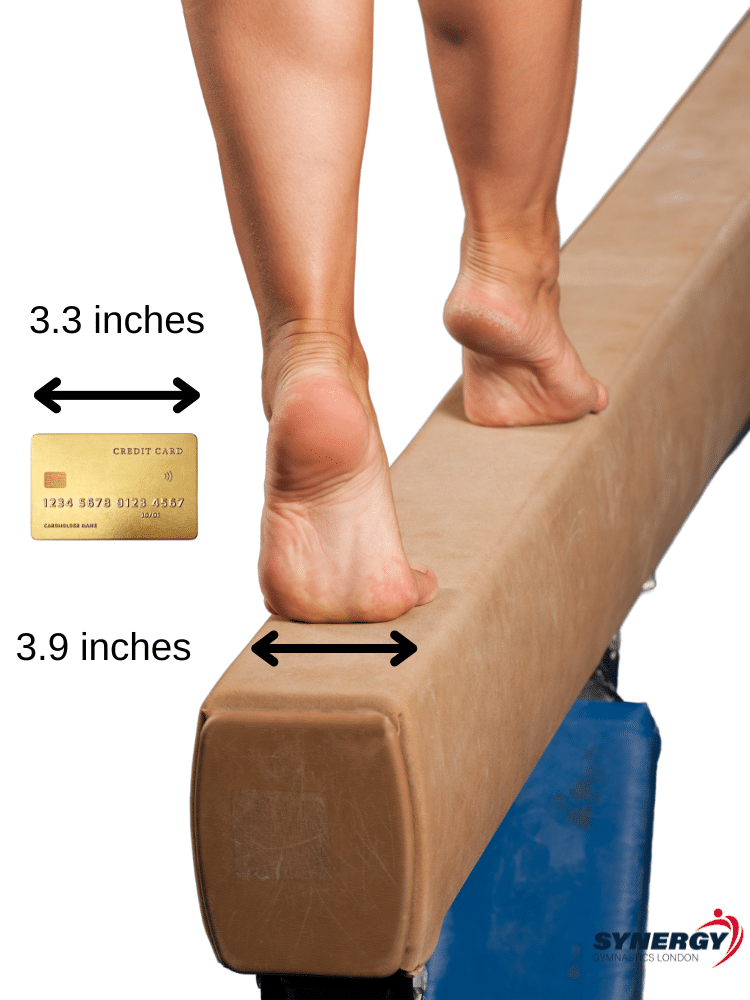

At less than 4 inches wide, the beam is arguably the scariest of all the apparatus. Gymnasts must have pinpoint accuracy when placing their hands and feet on the beam, especially as the skill level in elite gymnastics has increased hugely in recent years.

Let’s jump into the details of the Olympic balance beam!

What is the balance beam?

The balance beam is a rectangular-shaped apparatus and is usually just referred to as the ‘beam’. The beam is only competed only by female gymnasts and tests their ability to link dance, tumbling, jumps and leaps whilst staying in balance.

Gymnasts are expected to perform with elegance, and flair and demonstrate good posture throughout. A beam routine will finish with a dismount which is typically a tumbling move such as a somersault.

How wide is a balance beam?

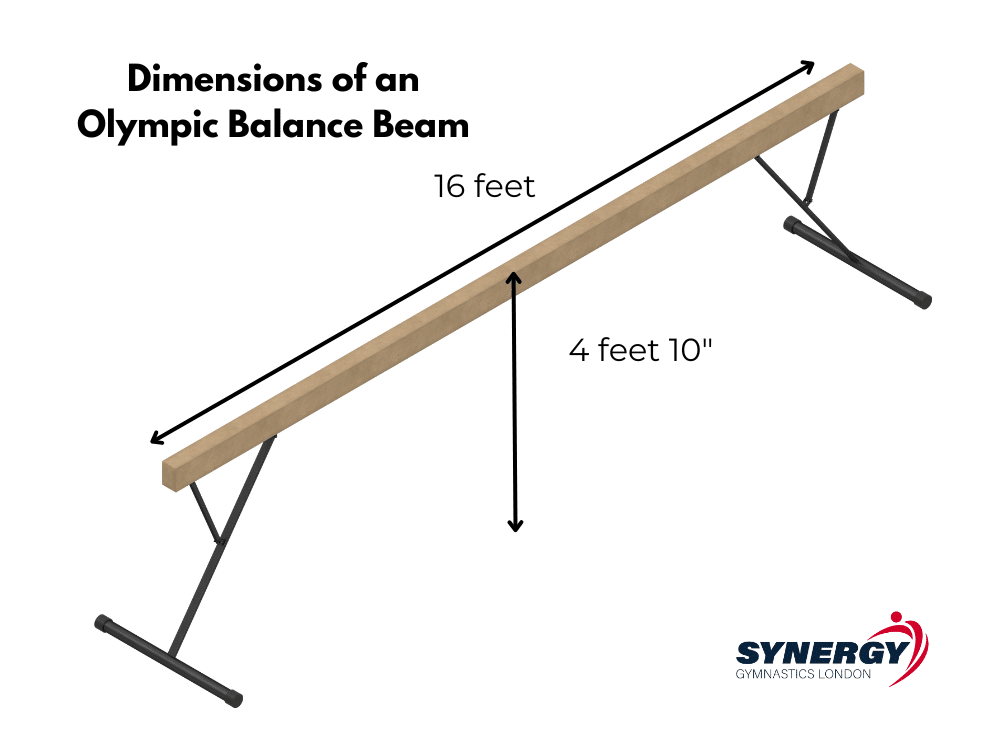

A full-size balance beam for female gymnasts is 3.9 inches wide.

It’s 16 feet long and at competitions, the beam is raised to 4 feet and 10 inches from the ground.

These measurements are decided by the Federation of International Gymnastics (FIG) but measurements vary for practice beams and beams for home use.

Balance Beams found in professional gym facilities will usually be around 4 inches wide so that gymnasts can get used to the incredible accuracy needed to compete on the beam from an early age.

Some beams will have height adjusters on the legs which allows them to move lower than the competition height down to as low as two or three feet. This creates a safer setup for younger gymnasts should they fall whilst practicing. Floor beams are also popular with coaches as they are just a couple of inches in height and often made from softer material to prevent injury.

What is a balance beam made of?

Competition standard beams are made from a hollow aluminum body and the padding material is suede. It is designed to stay fairly rigid – if it creates too much bounce gymnasts would find it hard to control their movements. On the other hand, if it stays to rigid, the gymnasts will be unable to absorb the impact from landings.

The main body of the beam is supported by legs at either end. The legs are usually metal and can be padded with foam to protect gymnasts from injury. At the bottom of the gymnastics beam, the legs will be anti-slip feet, often made from rubber and designed to keep the beam stable.

The image above shows the inside of FIG standard Gymnova Balance Beam with the end cap removed so that you can see inside of the beam. The end cap is there to protect the gymnasts from injuring themselves on the sharp metal end of the actual beam. It also hides the untidy part where the suede cover wraps inside giving a more professional look.

Beams used for practice at home or at the gym can vary in the materials used. Some balance beams are wooden and others are foam. Balance beam padding material includes leather or carpet as well as the usual suede used on competition beams. Some practice beams can be placed straight onto the floor so wouldn’t require legs.

Can you use a springboard for beam?

Yes, a springboard can be used to help mount the beam. This is when the gymnast performs a jump or acrobatic move to get onto the beam at the start of the routine. It’s optional and some gymnasts will find different ways of mounting the beam without a springboard.

If a gymnast falls from the beam mid-way through a competition routine they can’t use the springboard to restart.

Do you need mats under the beam?

Yes, you need mats underneath the beam as falls are common. You will also need matting at the end of the beam for the dismount and landing.

At elite-level competitions such as the Olympics, the matted area underneath the beam includes a landing area at either end. In total, the matted area measures 59 feet (18 meters) in length and is 13.1 feet (4 meters) wide with the beam placed in the center.

This leaves a landing area at either end which is 16.4 feet long by 6.5 feet wide (5 meters by 2 meters).

FIG standard landing mats are 7-7/8 inches (20 cm) thick.

Balance Beam History

Although women had competed in gymnastics at the Olympics since 1928, the beam wasn’t included until the 1952 Helsinki Games. Historically, gymnasts performed more dance skills on the balance beam. Leaps and handstands were common but tumbling skills were not seen until around the 1960s.

By the 1960s Back handsprings were included in Olympic-level beam routines but that would be the hardest level of skill. Difficulty levels increased sharply in the 1970s thanks to gymnasts such as Olga Korbut and Nadia Comaneci who would use more advanced tumbling and aerial skills in their routines.

As a result, the material used to make beams changed from wood to suede-covered surfaces in the 1970s making it safer and easier to perform harder skills. They were less slippery and allowed gymnasts to link more difficult moves together.

Soviet and Eastern European gymnasts dominated the early era of the Olympic balance beam. Kathy Johnson in 1984 was the first USA gymnast to win a balance beam medal at the Olympics when she claimed bronze. Since the 1990s China and the USA have been more dominant at the Olympic level than any other country.

Balance beam in the 1960s. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons / The Dutch National Archive

Balance Beam Scoring

At the highest level competitions such as the Olympic Games and World Championships, there are up to 12 judges responsible for the scoring process. A Balance Beam routine lasts between 70 to 90 seconds at this level.

- Difficulty Judges (D-Panel). 2 Judges will record which skills have been performed and add up how much each skill is worth to give a total D-Value (Difficulty score). The harder the skills, the higher the difficulty score. A routine must have a minimum of 8 individual skills (elements) and the 8 highest difficulty elements are counted towards the d-score.

- Execution Judges (E-Panel). 7 Judges analyze the performance and deduct points for any errors. E-Judges score out of 10.

- Time Judges. 2 Judges are responsible for timing. Gymnasts have a maximum of 1 minute and 30 seconds to complete the routine. If a gymnast fall they have 10 seconds to restart without losing additional points. If a gymnast falls but doesn’t restart within 60 seconds, the routine is finished.

Execution Judges mark their score out of 10 and analyze:

- Artistry

- Rhythm and Tempo

- Faults in the performance of each individual element

For small errors, execution judges will deduct 0.10, for medium errors 0.30 and 0.50 for large errors. The execution score is taken by averaging the 3 middle scores out of the 7 execution judges. This prevents an unusually high or low score from counting toward the final score.

Gymnasts can also be awarded additional bonus marks for performing certain skills or linking elements together. For example, 0.50 is awarded for acrobatic elements in different directions. The D-panel is responsible for awarding these scores which are known as ‘Compositional Requirements’ (CR).

The execution and difficulty scores are added together to give a total score.

The FIG (Federation of International Gymnastics) is responsible for governing the rules of gymnastics and produces a lengthy Code of Points which is essentially the rule book for the beam and all other gymnastics apparatus.

Types of Balance Beam Moves

The Code of Points produced by the FIG places skills into the following categories; Mounts, Turns, Acrobatic, Non-Acrobatic Holds, Leaps, Jumps and Hops and Dismounts. Each move is given a value and gymnasts have to include a minimum of 8 skills to compose a competitive routine.

Mounts

A mount is a move to get onto the beam at the start of the routine. This is the only part of the routine that can use a springboard if desired. Beam mounts for beginners would use a jump, Squat on or Straddle on (similar to a vault). Whereas a more difficult mount would be round off, back handspring or back tuck to land on the beam.

Some gymnasts mount the beam at the side but the majority will mount it from one end.

Dance

Dance-type moves include turns, jumps, leaps and hops, often choreographed to connect and make the routine flow. Unlike the floor exercise, there is no music to accompany the balance beam routine.

Turns are performed in a variety of body positions, usually on one leg and at different heights. Head position is key to keeping balance throughout a turn.

Split leaps, Sissone and Cat leaps are also examples of common skills included in beam routines. They can also be linked to the end of acrobatic skills to earn additional difficulty value.

Acrobatic

Acrobatic skills are flighted for example a back handspring or a somersault involves the gymnast completely leaving the apparatus. Acrobatic skills are very much like tumbling-type moves found in floor routines.

Performing these moves on a four-inch-wide beam is way more difficult than on a sprung floor though!

The margin of error is tiny but the rewards are high in terms of higher difficulty scores.

Acrobatic (non-flighted) and holds

Non-flighted acrobatic moves stay in contact with the beam at all times. For example a roll or walkover.

The difficulty level is generally lower compared to flighted moves as it should be easier to maintain balance in a non-flighted move.

Holds can include skills such as splits and handstands which should be held in a static balance for around 5 seconds.

Dismounts

A dismount is the final skill performed on the beam and returns the gymnast onto the mat, hopefully on her feet!

Somersaults are the most common dismounts at elite-level competitions, with most gymnasts performing double somersaults or somersaults with a twist.

Forwards somersaults are performed with a short run-up whilst backward somersaults would first require a round-off to land near the end of the beam.

How do you learn balance beam?

As with all gymnastics skills, you must break things down into smaller chunks and progressions.

Gymnasts begin learning the balance beam on low beams, floor beams and even lines on the floor. By starting at a lower height, there is less fear and less risk of injury. Coaches will also use a mat over the top of the beam to create extra padding and help build confidence to perform new skills.

Floor beams and low beams can even be used at home for extra practice.

Coaches will use lots of drills and progressions to encourage good posture on the beam. For example, when traveling along the beam a gymnast will need to keep looking forward (rather than at the floor). To encourage the correct head position, coaches place a bean bag on the gymnasts’ heads. If it stays on the head, the position is good.

Likewise, cones can be placed on the beam as obstacles for gymnasts to jump over. This helps build confidence in jumping and landing in balance on the beam.

Sign up for a free trial session here at Synergy Gymnastics and we’ll help you learn the balance beam in a safe and friendly environment.

What is the hardest move on balance beam?

Gymnasts can often get mental blocks when training harder moves on the balance beam. These can happen with a variety of skills and are specific to each gymnast. They may have had a bad experience attempting a skill and this will make it harder to perform the next time.

A new move with a higher level of difficulty is named after the gymnast who first performs it. This gives gymnasts an added incentive to push the boundaries of what’s possible.

The FIG Code of Points categorizes each skill that can be performed on the beam. Some of the skills with the hardest difficulty values (group G / H) are:

- The Biles. H-Rated. The only H-rated skill on beam is named after Simone Biles. This is a dismount skill performed at the end of the routine. The Biles is a double twisting double somersault (also called full-full or double-double for short). Many commentators felt the H-Rating was unfairly low considering the extreme difficulty however the FIG was not swayed to give it any more than a H-Rating.

- The Garrison. G-Rated. The Garrison is a mount skill where the gymnast performs a round off onto the springboard followed by a Layout Full Twist to land on the beam. It’s named after American gymnast Kelly Garrison.

- The Erceg. G-Rated. This is an Arabian Somersault onto the beam. The gymnast performs a round off onto the springboard followed by a half turn into a forward somersault. The Erceg is named after Tina Erceg from Croatia.

- The Patterson. G-Rated. This skill is a dismount named after the USA gymnast Carly Patterson. The Paterson is a double Arabian somersault – Round off, into a half turn then a double forwards somersault. Because the gymnast is traveling forwards it is impossible to spot the landing early.

- Layout Full Twist. G-Rated. This skill is difficult because the twist in the somersault means the gymnast has to control two directions – the rotation of the somersault as well as the pull of the twist. Spotting the beam early is key to holding the landing. It can be performed from round off or from back handspring.

There are numerous difficult balance beam moves that are no longer seen including The Worely and The Li Turn.

Who are the best gymnasts at beam?

Anyone who has won an Olympic Medal or has a beam move named after them must be good!

- Heine Araújo (Brazil)

- Simone Biles (US)

- Guan Chenchen (China)

- Nadia Comăneci (Romania)

- Tina Erceg (Croatia)

- Kelly Garrison (US)

- Cristina Elena Grigoraş (Romania)

- Shawn Johnson (US)

- Svetlana Khorkina (Russia)

- Olga Korbut (USSR)

- Dina Kotchetkova (Russia)

- Deng Linlin (China)

- Nastia Liukin (US)

- Li Li (China)

- Shannon Miller (US)

- Henrietta Ónodi (Hungary)

- Cătălina Ponor (Romania)

- Sanne Wevers (Netherlands)

- Liu Xuan (China)

Sources

Women’s Artistic Code of Points (FIG)

- How to Do a Back Handspring: Complete Step-by-Step GuideLearning how to do a back handspring is an exciting milestone for any gymnast. It builds confidence, agility, and forms the foundation for advanced tumbling… Read more: How to Do a Back Handspring: Complete Step-by-Step Guide

- How To Get Over a Mental Block In Gymnastics: A Complete GuideGymnastics is a sport that requires not only physical strength and skill but also mental strength. When a gymnast feels like they cannot attempt a… Read more: How To Get Over a Mental Block In Gymnastics: A Complete Guide

- The Best Leotard for Girls in 2025: What to Look ForFinding an ideal leotard for girls isn’t just about picking a dazzling design that sparkles (although it does help!). The leotard has to fit perfectly,… Read more: The Best Leotard for Girls in 2025: What to Look For

- The Best Gymnastics Shorts (Our Top Picks)The best gymnastics shorts are designed to be worn over the top of a leotard providing additional coverage around the upper legs, whilst allowing gymnasts… Read more: The Best Gymnastics Shorts (Our Top Picks)

- Decathlon Leotards – Are They Any Good?If you’re in the market for a new leotard, you may be wondering if Decathlon leotards are any good considering the low cost of their… Read more: Decathlon Leotards – Are They Any Good?

- A Complete Guide to Gymnastics Hand RipsAre you tired of dealing with painful gymnastics rips on your hands from training? Look no further – this article offers a comprehensive approach to… Read more: A Complete Guide to Gymnastics Hand Rips