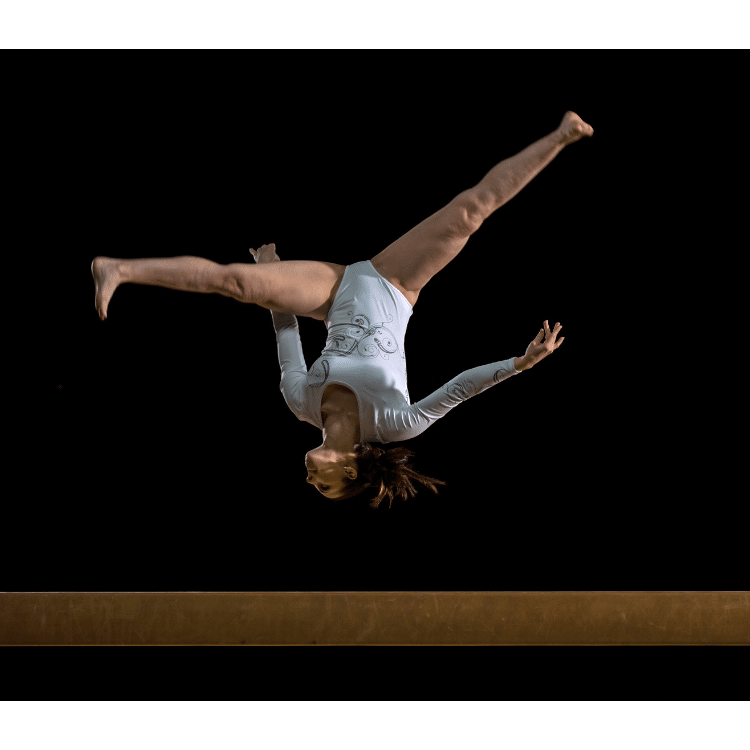

The balance beam is one of the most challenging apparatuses in women’s artistic gymnastics. Performing skills on a thin beam less than 4″ wide and 4 feet off the ground requires immense skill, balance and courage.

While the sport has evolved rapidly, with gymnasts performing increasingly difficult skills, there are some skills that were once popular but are now rarely, if ever, performed in competition.

Here are 6 beam skills that have been largely forgotten in modern gymnastics.

1. Tsukahara Dismount

The Tsukahara is a family of aerial skills named after Japanese gymnast Mitsuo Tsukahara who pioneered several variations in the 1950s and 1960s. The most common Tsukahara dismount off-beam is a backwards salto tucked.

This dismount was very common in the 1960s and 1970s. Larisa Petrik of the Soviet Union famously performed a Tsukahara dismount during her gold medal-winning beam routine at the 1970 World Championships. During the 1980s, as gymnastics difficulty increased rapidly, the Tsukahara dismount declined in popularity in favor of higher-rated dismounts like double salto variations.

While the Tsukahara dismount is still technically feasible to perform today, it is valued at only a D difficulty score, making it easy for gymnasts to gain more points from other more difficult dismounts. The last prominent use of the Tsukahara dismount was by Henrietta Ónodi of Hungary who performed it consistently during her competitive career in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

2. Silivas Mount

The Silivas is an acrobatic mount onto the beam invented by Romanian gymnast Daniela Silivas. It consists of a Neck Stand (yes, it was a thing!) with a half turn whilst inverted.

Silivas unveiled this creative beam mount during her dominant run to the 1987 World Championship title, where she utilized it to mount and then again in combination later in her routine. The difficulty of mounting onto the narrow beam surface in a splits position whilst resting body weight on the neck made it an impressive and unique skill that other gymnasts struggled to successfully replicate.

The Silivas beam mount became somewhat popular as an opening skill through the late 1980s and early 1990s. Prominent gymnasts like Gina Gogean of Romania and Henrietta Ónodi of Hungary incorporated it into their routines. However, the high-risk nature of the skill and difficult body position in landing on the beam in cross-sit proved too challenging for most gymnasts to perform consistently.

By the mid-1990s, the Silivas mount had largely disappeared from beam routines. While it remains in the Code of Points today carrying an ‘F’ difficulty value, the extreme difficulty and high risk of falling keep it from being performed by elite gymnasts. It remains an impressive display of acrobatic and beam control when landed successfully.

3. The Teza

The Teza was a skill first performed on the beam in the late 1990s. It is named after French gymnast Elvire Teza who pioneered the skill.

The Teza consists of a full twisting back handspring into back hip circle whilst side onto the beam. This skill showcased difficult acrobatics, precision and the ability to link two skills smoothly. When Teza successfully unveiled it in competition, it gained some brief popularity with other top gymnasts.

However, the catch of the beam at the end of the back handspring was particularly brutal on the gymnasts hips and stomach.

By the early 2000s, the Teza had been downgraded in difficulty and faded from use completely. No major gymnasts competed the skill at events and the back hip circle become very rare after updates to the FIG Code. The extreme precision and arm strength required to perform the Teza safely made it an unreliable skill that challenged even the best beam workers of the late 1990s era.

4. The Worely

Possibly the most unique skill in this article is named after its creator and the only gymnast to perform it in a major competition, American Shayla Worley.

The Worley starts as a Back Handspring but the gymnast completes a half turn before the hands are placed so they finish facing forward like a front handspring would do.

First performed in 2007, it was never picked up by any other gymnast probably because of the high level of precision needed. The skill received an upgrade in the Code of Points in 2017 but this still did not encourage any gymnasts to include it in their routines.

5. The Li Turn

This turn skill was unveiled to the world by Chinese gymnast Li Li in 1990.

When done successfully the Li involves spinning on the back one and a quarter times whilst the legs are in the Kip position. It showcased balance, control and grace on the beam and helped transition into moves low to the beam or even underneath it.

By the mid-1990s, the Li Turn had grown into a popular element on beam. Prominent gymnasts utilized it during their routines but the coordination and precise technique required to perform the continuous spin without error proved difficult for many gymnasts to develop consistently.

As acrobatic skills advanced, the Li Turn decreased in popularity in favor of higher difficulty. By the early 2000s, it was rare to see in elite routines. While visually impressive when performed correctly, the Li Turn has been largely forgotten today as skills of greater difficulty have developed. Even an upgrade in the 2017 code of points has had little impact.

6. The Dunn Mount

The Dunn Mount involves a Back Handspring with a half turn into a forward walkover. First performed by Australian Jacqui Dunn it is also known as the Onodi Mount or Arabian Walkover Mount.

This is a distinctive but rare mount. When a gymnast pulls it off there is no doubt it looks visually stunning however the precision needed is very high. Gymnasts are only able to spot the beam very late owing to the half turn, and a minor error will cause the routine to be over before it’s even started.

The Dunn Mount was yet another beneficiary of the 2017 upgrades to difficulty values in the code of points however, still very few gymnasts choose to use this mount in their routines.

Conclusion

Artistic gymnastics has rapidly evolved over the decades, with each generation of gymnasts striving to perform ever more challenging skills. In this drive for increased difficulty, some unique skills have been left behind and forgotten. These beam skills may no longer be competitive but were important innovations in their time that entertained crowds and pushed boundaries in the sport’s development.

They serve as reminders of the remarkable creativity, athleticism and grace on display in women’s gymnastics.

Interested in learning balance beam skills in a professional gym? Book a free trial here at Synergy Gymnastics on our parent portal.

- How To Get Over a Mental Block In Gymnastics: A Complete GuideGymnastics is a sport that requires not only physical strength and skill but also mental strength. When a gymnast feels like they cannot attempt a… Read more: How To Get Over a Mental Block In Gymnastics: A Complete Guide

- Find The Best Leotard For Girls (Guide)Finding an ideal leotard for girls isn’t just about picking a dazzling design that sparkles (although it does help!). The leotard has to fit perfectly,… Read more: Find The Best Leotard For Girls (Guide)

- The Best Gymnastics Shorts (Our Top Picks)The best gymnastics shorts are designed to be worn over the top of a leotard providing additional coverage around the upper legs, whilst allowing gymnasts… Read more: The Best Gymnastics Shorts (Our Top Picks)

- Decathlon Leotards – Are They Any Good?If you’re in the market for a new leotard, you may be wondering if Decathlon leotards are any good considering the low cost of their… Read more: Decathlon Leotards – Are They Any Good?

- A Complete Guide to Gymnastics Hand RipsAre you tired of dealing with painful gymnastics rips on your hands from training? Look no further – this article offers a comprehensive approach to… Read more: A Complete Guide to Gymnastics Hand Rips

- Is Gymnastics Dangerous? (Facts and Comparisons)Gymnastics is acknowledged as a highly technical and physically demanding sport. It inherently carries a risk of injury, which is why most coaches and clubs… Read more: Is Gymnastics Dangerous? (Facts and Comparisons)